NEIL KEARNEY

On the Friday afternoons when the drivers practised ahead of the motor racing at Longford, Tasmania our schoolteachers desperately fought losing battles to keep us in class.

As the roar of engines sent shivers up our spines and the excitement swelled within every child, the teachers eventually relented, throwing their hands in the air and pointing us towards the bicycle sheds.

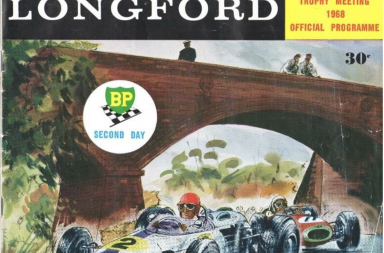

That was the signal for a Le Mans start. We jumped on our bikes, pedalled madly to pub corner and grabbed front position behind the hay bales. ‘Protected’ from danger, we watched wide-eyed (or eyes shut) as the motors thundered and thumped around pub corner, sometimes scraping the trees on their way out of the right-hander.

Motor racing was another world. It was loud, pungent, violent, expensive and completely foreign to life in a tranquil country town. In the early ‘60s, most Longford families were just discovering television and were intrigued by the test pattern, not to mention the foreign accents on shows like Gomer Pyle and The Mickey Mouse Club. Looking back 50 years to the last long weekend of motor racing at Longford, it all feels like a very long time ago, a very different time. It still seems bizarre that a country town in Tasmania could attract the fastest and most famous racing drivers on the planet.

To us, those thunderous racing cars came from another world. They were shaped like rockets. The men piloting them resembled spacemen. They seemed indestructible.

But that perception changed on Friday February 28, 1964.

During the afternoon practice session, standing on the outside of pub corner, we schoolkids heard a wild explosion as a racing car coming off Kings Bridge at over 160 km per hour slammed into a tree, just 300m from where we stood.

The impact propelled the driver through the air and his body landed in the middle of the road, directly in front of us. The engine of his Cooper racing car catapulted and rolled to within a few metres of where we stood.

More than fifty kids were grouped right behind the hay bales. We watched, mouths agape, as the driver lay motionless on the asphalt. Slowly, the ambulance drove away. That night a neighbour told us the man killed was an American named Timothy Mayer. For many of us, that was the first time we had seen death.

We knew nothing about Timmy Mayer, except that he was a young American. To us, the foreign drivers were exotic figures from faraway lands. Everyone recognised Jack Brabham because he was the dinkum Aussie icon. A tin badge with Jack’s photo was the children’s admission pass into the Longford motor racing. We had local heroes too – the Youl brothers from Symmons Plains and Longford’s own Gene Cook, who was a cult figure at Shackie’s garage. In the ‘60s ‘Cookie’ was even more of a star to Longford kids than Barry Lawrence, the footballer who would later captain Victoria, and Max Baker, the champion jockey who became the first person inducted into Racing Tasmania’s Hall of Fame. ‘Cookie’ was a daredevil. When he rounded pub corner, usually throwing his sedan perilously close to the line of trees, the local kids roared so loudly they’d almost drown out the engine noise.

Timothy Mayer’s accident was front page news on the Saturday edition of The Examiner, but any reflection on his life was soon overtaken by interest in the weekend’s racing.

But, thanks to the internet, we now learn that Tim Mayer packed a lot into his twenty-six years. He was from a wealthy Pennsylvania family. His uncle was State Governor. Tim gained a degree in English literature from Yale University. He was married, an emerging superstar, tall, athletic and charming.

He had already developed a reputation as a very fast driver. In early 1964 he joined Kiwi Bruce McLaren for the Tasman series, racing across New Zealand and Australia in custom-built cars. It was the McLaren team’s first championship entry.

In the weeks before Longford, Mayer finished third at Warwick Farm, ahead of the 1962 world champion Graham Hill, and then at Lakeside he led Jack Brabham before being forced to retire with engine problems. In those days, open wheelers cars had a tube frame, a big fuel tank and a vibrating engine. Drivers and their families were matter-of-fact about the risks. The wife of one world champion used to pack a black dress whenever she travelled to Grand Prix meetings with her husband. The dress was in case she had to stay around for a funeral.

After Timmy Mayer’s death in the Friday practice session, Bruce McLaren didn’t race at Longford on the Saturday.

On the Monday – three days after Tim’s accident – McLaren started from the back of the grid in the feature race, the final round of the Tasman series.

McLaren drove brilliantly, passing every other driver except Graham Hill.

His second placing helped Mclaren to clinch the Tasman series title, ahead of triple world champion Jack Braham. It was Bruce McLaren Motor Racing’s first championship victory.

These poignant words were written by Bruce Mclaren about Timmy Mayer in the days after Mayer’s accident:

“The news that he died instantly was a terrible shock to all of us. But who is to say that he had not seen more, done more and learned more in his 26 years than many people do in a lifetime? It is tragic, particularly for those left. Plans half-made must now be forgotten and the hopes must be rekindled. Without men like Tim, plans and hopes mean nothing. To do something well is so worthwhile that to die trying to do it better cannot be foolhardy. I can’t say these things well, but I know this is what I feel to be true. It would be a waste of life to do nothing with one’s ability. Life is measured in terms of achievement, not in years alone.”

Bruce McLaren, New Zealand’s champion driver, builder and inventor, was 32 when he died in a crash at Goodwood, England. Several heroes of Longford’s long weekend were killed during this tragic era, among them the winner of the last feature race at Longford, Piers Courage, who was heir to the Courage brewery dynasty.

The remarkable family stories of McLaren and Mayer carried on.

Tim’s older brother, Teddy, was distraught at his brother’s passing but continued the family’s passion for racing – Teddy built the McLaren racing legend. After Bruce’s death, he became boss of the McLaren Formula One team and took it to two world championships.

Teddy named his son Tim in honour of his younger brother who died at Longford. Timothy A. Mayer 11 became one of the most powerful figures in motor sport. He was chief operating officer of the International Motor Sports Association and the American Le Mans series.

At Longford, the place where Tim Mayer hit the tree was marked by a memorial stone – until it was relocated inside the Country Club hotel. The helmet that Mayer wore was on display in the hotel for many years.

The motor racing at Longford left its mark in so many ways on participants, officials and spectators.

For those who witnessed Timmy Mayer’s accident in 1964, they’ll never forget that fateful Friday afternoon.

www.neilkearney.net.au